4 of 5 stars

A fascinating President who deserved a less subjective biography. Monroe by himself is due five stars, but the fawning, blind-eye treatment by Unger diminishes rather than elevates. I can't think of one situation where Unger finds fault in his hero. If recent historical biographers (from Vidal to Ellis to McCullough to Chernow) allow us to see and relish in the founding generation -- warts and all -- why isn't James Monroe, who certainly deserves to be in the pantheon of greatness, afforded this honesty. For example, while many of his contemporaries were embracing manumission either personally or as the requirement of a great nation, Unger simply states: "Monroe had no strong objection to slavery." This is particularly concerning because the conversion of the economy in the South from the tobacco base in the days of the framing of the Constitution to the cotton base in the early 1800's changed slave existence dramatically on Monroe's own lands -- from a crop delicate enough to require worker contentment to a significantly more brutish existence. Unger passively even observes: "Cruelty replaced paternalism across the South." Thus, the Missouri Compromise, reached in Monroe's second term, which extended slavery to the new territories is favorably viewed by Unger, as a furthering of Monroe's Era of Good Feelings, rather than the seminal foreshadowing of the Civil War.

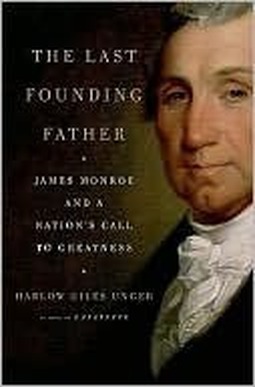

Despite, rather than because of, this lack of subjectivity, "The Last Founding Father" is a great read and does put Monroe in his proper place in history as a result of the impact of his actions and sacrifices. Though Unger is lavish with his praise of Monroe, he often feels compelled to take it even a step further by undergirding his thesis of Monroe-greatness with a diminishment of those around his central figure. "Washington's three successors -- Adams, Jefferson, Madison -- were mere caretaker presidents who left the nation bankrupt, its people divided, its borders under attack, its capital city in ashes." Well ... Monroe was a significant player in both the Jefferson and Madison administrations and much of the opportunity for Monroe's Era of Good Feelings was laid in these prior administrations. Is Monroe great because of timing or personal contribution? A less biased biographer would have found more in the balance.

But perhaps the most blatant case of compliment by diminishment comes around the foundational "Monroe Doctrine." Unger seeks to destroy any assertion that Monroe's proclamation was not entirely his own creation. Especially not John Quincy Adams. He calls the suggestion "ludicrous" and demeans Adams diplomatic experience. He states that Monroe's eight years as a diplomat was far more taxing than Quincy Adam's five years of "dinners, balls, parades, receptions in St. Petersburg, Russia with his friend the czar." But, hidden in the notes for the chapter is this draft proposal from Adams: "the American continents by the free and independent condition which they have assumed, and maintain are henceforth not to be considered as the subject of future colonization by any European power." That is the essence of the Monroe Doctrine ... the fact that it came from a open recommendation of his Secretary of State should not be hidden by his biographer or be diminished as mere "parroting" of an earlier Monroe warning. If Monroe is to be valued in the wisdom he showed in his formative ministerial roles, can he not also be valued in listening to his own ministers? Harlow Unger, I think you protest too much.

Unger does present a very interesting contemporary current in Monroe's evolving view of the role of government. Monroe was present at both the American Revolution (staff to Washington) and the French Revolution (American Ambassador). At first, like Jefferson he fails to distinguish the two. This unified view frames revolution as about the expansion of human liberties. As a result of Napoleon's policy reversal re Spain and Florida, however, he understands something which was never fully comprehended by his mentor: protection of national interests was the raison d'etra of all governments, whether born of revolution or not. Expansion of individual liberties had simply been a by-product of the American Revolution because it was essential in uniting the American people and, therefore, in the national interest. Tyranny -- indeed Napoleon -- had been the by-product of the French Revolution, because it was essential for maintaining the unity of the French people. The US foreign policy still struggles with this lesson. The core outcome in revolution is what brings unity (beyond throwing the bastards out). We can't assume that it will always be democracy, even in the headiest revolution in the Middle East.

Parallels abound between Monroe and later Presidents. Monroe was central to expanding exponentially the territory of the United States (Louisiana Purchase which he negotiated with Talleyrand) as was Polk (Mexican War). Monroe sought permission from the President to lead a army in the War of 1812, as Teddy Roosevelt had petitioned Wilson during the First World War. Monroe failed to adequately pass the baton to a successor (John Quincy Adams v. Andrew Jackson) like Clinton to Gore which served to create a vacuum wherein many of his successes were reversed.

Monroe was a states rights republican who was, in John Quincy Adams words, "strengthening and consolidating the federative edifice of his country's Union, til he was entitled to say, like Augustus Caesar of his imperial city, that he found her built in brick and left her constructed of marble."

To be tweeted links to my new posts -- blog, book reviews (both nonfiction and fiction), data or other recommended tools -- just go to my Home page and click on the Twitter button on the right, just above the tweet stream, and follow me @jcrubicon.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed